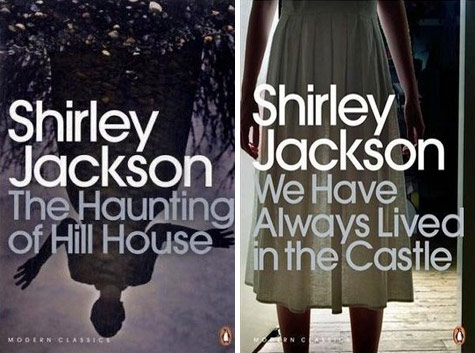

Many think of Shirley Jackson primarily as a short story writer, due to her much-anthologized classic “The Lottery.” But for me it’s Jackson’s novels that really demonstrate her lasting contribution to her field.

The most widely-read of these, The Haunting of Hill House, is an amazing literary ghost story. Don’t be put off by the uninspiring 1999 film adaptation “The Haunting,” which scraps the novel’s texture, humor, and carefully-crafted ambiguities in exchange for campy CGI. The film’s inadequacy isn’t wholly its fault. It’s difficult to imagine a successful adaptation. The Haunting of Hill House uses its close, third-person perspective to give readers an exquisitely familiar knowledge of Eleanor, its shut-in, troubled protagonist. This lends itself very well to the novel’s liminal, psychological treatment of its horror premise, and can’t be easily replicated by the comparative “objectivity” of film.

The rhythm of Jackson’s prose is off-putting in its strangeness, yet catching—you’re swept into it very quickly, as though by a strong current, and you begin to think in the books’ patterns. The snippet of text below comes from Eleanor’s initial journey to Hill House in the novel. It shows Eleanor’s dreamy, susceptible personality, even before the house’s atmosphere of paranoia starts to seriously affect her. It also displays Jackson’s skill at depicting her characters’ interiority via their encounters with the exterior world. And it’s a simple, beautiful moment of language.

Eleanor looked up, surprised; the little girl was sliding back in her chair, sullenly refusing her milk, while her father frowned and her brother giggled and her mother said calmly, “She wants her cup of stars.”

Indeed yes, Eleanor thought; indeed, so do I; a cup of stars, of course.

“Her little cup,” the mother was explaining, smiling apologetically at the waitress, who was thunderstruck at the thought that the mill’s good country milk was not rich enough for the little girl. “It has stars in the bottom, and she always drinks her milk from it at home. She calls it her cup of stars because she can see the stars while she drinks her milk.” The waitress nodded, unconvinced, and the mother told the little girl, “You’ll have your milk from your cup of stars tonight when we get home. But just for now, just to be a very good little girl, will you take a little milk from this glass?”

Don’t do it, Eleanor told the little girl; insist on your cup of stars; once they have trapped you into being like everyone else you will never see your cup of stars again; don’t do it; and the little girl glanced at her, and smiled a little subtle, dimpling, wholly comprehending smile, and shook her head stubbornly at the glass. Brave girl, Eleanor thought; wise, brave girl.

Haunting is stunning, and while it’s a must-read for anyone interested in ghost stories, haunted houses, or psychological horror, it also stretches beyond its demographic. If the aforementioned narrative elements do less-than-nothing for you, I’d still recommend reading a few pages and seeing whether Jackson’s unique style draws you in.

If you’ve already read Jackson’s most famous novel, or if you’d just like to start with something different, We Have Always Lived in the Castle is an excellent choice. I think it gets less academic and popular love than Haunting (which dovetails neatly with liminal gothic novels like Turn of the Screw and thus, I believe, show up on syllabi more frequently), but is perhaps the more interesting book.

Some years before the novel opens, the large, wealthy Blackwood family was almost entirely wiped out over the course of a single dinner by an unexplained arsenic poisoning. The only survivors were Constance, the eldest daughter of the house; Merricat, the youngest; and their elderly Uncle Julian. All of them have been marked by the experience. Constance is now agoraphobic. Merricat has almost gone feral. Uncle Julian, who barely survived the poison, remains weak, addled by its after-effects. They live reclusively in their estate, which is falling into disrepair. They are feared and hated by the people of the nearby town, who simultaneously resent the Blackwood’s privilege (even though it’s in decline), and the transgressions against the moral order the mysterious poisoning implies.

Like Thomas Hardy, Jackson is big on evocative description of environments. The Blackwood “Castle,” the forest that surrounds it and the village beyond it are, like Hill House, fully realized, dense, and smotheringly sensual. You cannot escape forming not only pictures of these homes, but whole floor plans, even if, like me, you’re not a visually-minded reader.

Space, as I mentioned earlier, is intensely important to Jackson, who herself became agoraphobic later in life. We Have Always is an evocative portrait and exploration of that condition. The girls physically and mentally construct elaborate narratives of food and home, despite and because of such narratives’ disruption by the multiple-murder. Constance—who stood trial for poisoning her family, perhaps accidentally, perhaps on purpose—gardens and cooks, preserves and serves, all day, every day.

Merricat practices her own personal form of protective domestic witchcraft, more based on spells than jam. Her system of magical thinking is at once primitive and shrewd. Merricat is a sharply intelligent child who’s drifting away from the influences of the wider world. She refers to an unbreakable continuity of Blackwood Women (“the Blackwood Women have always”), and of Constance as the inheritor of these traditions, while she herself—never womanly in any sexual sense—is always divorced from them. Her trajectory suggests the frightening and seductive possibility of a life wholly detached from, and at odds with, broader social frameworks. Only the most elemental and primitive of these survive—and even these bonds are denatured and warp into strange configurations. The strength of Merricat’s personality bewitches readers, forcing them into an uncomfortable position of unsentimental empathy with her.

Her more literal witchcraft is no less effective. Cousin Charles, a relative who attempts to ingratiate himself with Constance for the family’s remaining money, is banished by Merricat’s rites, even if he cannot be initially warded off by them. Some might want to quibble about the degree to which the book is truly fantastic. But Merricat’s fantastic rules and rituals are real for her, whether or not they’re real for her world (something that’s never entirely clear), and they have real, sometimes devastating, consequences. Her magic is a system of control which helps her cope with the assaults of the outside world. When this is breached, the girls are pushed towards Merricat’s ultimate refuge—her dream of “living on the moon,” in total isolation.

There’s a hysteria-like continuum between madness and femininity here—and between the strength conferred by both. This power opposes the power of strong, sane, young men, who are actors in the outer, rational world, who are governed by rules about behavior and relationships outside the domestic family unit. Mad Uncle Julian, Constance, and Merricat are removed from that exterior world—exiles, outcasts, and fugitives.

We Have Always is haunting and otherworldly; frightening, transcendent, common-place and glorious as a fairy tale should be. The conclusion simultaneously fulfills a modern narrative possibility—women living on the margins of a small community, in a sort of Grey Gardens scenario—and harmonizes with the destinies of mythical, fairy-tale women. The book is open to several such fantastic readings, all of which are somewhat true. By the end of the novel, Merricat has become the witch who captures Rapunzel and keeps her from all men’s eyes, the witch with the gingerbread house that children are warned not to touch. Meri and Constance have simultaneously become goddesses. They are brought offerings of food. Meri’s cat Jonas is her familiar, and her totem, putting Merricat in a context with Bastet or Freyja or their earthy witch descendents. Constance is the Vesta of the piece, ever tending the fire, ever loyal and homey. Constance and Merricat are Weird Sisters: too intimate a duo to admit a third and comprise the traditional trio.

Jackson’s work draws on the female gothic tradition, and circles a corpus of core themes: the body itself, food and providing, ideas of home, the interactions of psychology and places, and familial or sexual relationships between women. This focus doesn’t feel repetitive, or like rehashing. These are simply the topics Jackson’s compelled to write about, and that compulsion manifests itself as a series of intriguing efforts to map her chosen territory. If you haven’t discovered her (and she’s one of those writers where it feels like a discovery, intimate and profound), or if you haven’t gotten around to either of these books, I strongly recommend them. If you’d like to recommend or talk about other Jackson titles or similar work, please do so in the comments, because I for one would be delighted to hear about it!

Erin Horáková is a southern American writer. She lives in London with her partner, and is working towards her PhD in Comparative Literature at Queen Mary. Erin blogs, cooks, and is active in fandom.

Thanks for the post! Everyone needs to know about these incredible books. The timing was a weird coincidence for me because the browser tab I closed before opening Tor.com was the wikipedia page on

The Haunting of Hill House. I discovered these two books this summer, and they are now among my all-time favorites. I listened to the audiobooks narrated by Bernadette Dunne, who does a brilliant job with both. The Haunting of Hill House is even better if you listen to it at night with the lights out. I want to read her earlier novels, but haven’t yet.

The 1963 movie adaptation is actually one of the best and scariest “horror” movies ever made, IMHO. Hardly any special effects, just mood and atmosphere.

I really need to re-read these books! I read a bunch of Shirley Jackson’s short stories, novels, and nonfiction pieces waaay back in middle school and loved them, but haven’t re-read any of them for over 20 years now. Now I’m going to try to hunt them down! (I don’t know if you’ve found this in London, but for me, one of the only downsides of being an American expat in the UK is that, since there are different “classic” authors in the 2 countries, I have a hard time finding the older books I somehow expect to find in libraries. There are lots of lovely Stella Gibbons novels I might not have ever found in American libraries, but no Dashiell Hammett or Shirley Jackson novels in my local library! It’s great in helping me discover new-to-me authors, but it can still feel oddly disconcerting.)

@RDBetz, I completely agree. My family watch the 1963 adaption every Halloween growing up and it still gives me chills.

I had never heard of Shirley Jackson but my seventh grader will be reading Castle this year for school. I will have to read along.

@@@@@ 5.Marg I’d definitely recomend trying it! That’s a really interesting choice for 7th graders, ambitious.

@@@@@RDBetz & @@@@@Bittersweet Fountain I’ve been meaning to check it out, and this is really strong encouragement. Thanks!

@@@@@brentus I completely agree, re: people needing to know! And I’d love to hear about her other novels–I’ve read some scholarship about them but not the books themselves. I’m slightly put off by the summaries, which don’t sound fabulous, but I do trust Jackson.

@stephanie Burgis Man that is a strangely big expat irritation of mine as well? I remember the lulz that ensued among everyone-but-me when I didn’t know who Mathew Arnold was. How not to make an impression first day of grad school. :/ (No one cares about him but you, England. No one but yooooou.) Not sharing the same frame of references, when the shared language gives this illusion of cultural commonality, can make you feel/seem really ignorant. And suddenly the cultural information you *do* know, and the network of references you’ve cultivated over a lifetime of living in a country and relating to everything from art to grocery stores, looses most of its meaning and value. It might almost make more sense if you moved to Mongolia or something, because then no one would expect you to have a native level of knowledge of place, and you wouldn’t expect it of yourself.

Plus the UK failure to know who the hell Tony Kushner or Robert Penn Warren are: just annoying! I mean I’m happy to discover new texts/find that other people have heard of Angela Carter (though now she’s not just special to meee anymore, *brief hipster pout*, etc.). But I also sort of wonder at what point the Bill Bryson effect will set in and I’ll pretty-much-get the new cultural context, and won’t be thrown on a daily basis by stuff like ‘jolly hockey sticks’. It’s been like three years, come on, self.

Speaking as a Brit, may I apologise on behalf of my compatriots for having our own literary culture and not being fully educated in that of another country’s:)

In my experience, the 1963 film is well known and appreciated over here, it is possible that people don’t know that it’s based on a novel but not in my experience. Agreed, btw, that it is arguably the finest ghost film ever made (though I would argue for either Dead of Night or The Innocents).

For those who like haunted house stories, may I recommened A Garden Lost In Time by Jonathan Aycliffe and The Little Stranger by Sarah Walters, though these are both English writers so maybe not!

I too read “Haunting” for the first time this summer after intending to read it for so long. I enjoyed it immensley, though I think I prefer “Castle.” But it’s hard to go wrong with Jackson. She is the absolute master of melding mood and atmosphere with point of view (whether it’s 1st person or 3rd).

Add my voices to those encouraging you to check out the original movie version of “Haunting.”

@stephanie Burgis: I came across an edition of “Castle” at the Hodges- Figgis in Dublin this summer, so I’m assuming that it would be likewise available in the UK.

@a-j: No need to take offense. Stephanie wasn’t slamming BritLit. No serious reader would. She was just expressing frustration at not being able to find one of her favorite authors. After all, a British expat could come to America and enjoy Hershey Bars while still longing for the occasional Yorkie.

@a-j It definitely goes both ways–I find the unpopularity of Kushner here annoying, they find that I don’t know Mathew Arnold baffling, etc. Asked some Brit genre-fans just now if they were familiar with film and got a no and a tepid maybe. I’m told it perhaps has a cult following, and though that’s something it’s rather different.

My partner loves Sarah Waters, but “Little Stranger” is her least favorite by far.

@wizard Clip Nicely put, and I’ll certainly track it down!

On the 1963 film, if I recall correctly, the writer and director (Nelson Gidding and Robert Wise) actually consulted with Shirley Jackson about some of the interpretations they made while adapting the film. And I think she was okay with shortening the title as well, like she’d actually considered the shorter title for the novel at one point. Think this is discussed on the commentary track of the DVD release, which was recorded while all the major participants in the film were still alive. (Might have been recorded for the laser disc in the early 90s.)

There are some changes from the book, actually, and Eleanor’s a little bit different in the film, but I think the changes work well enough. (Then again, I saw the movie first.) It is quite an effective film. It does a very good job of slipping into and out of a subjective perspective tied to Eleanor. Excellent use of sound and cinematography.

The problems with the 1999 version are less the result of an incompatibility of the film medium with the novel and more the result of an incompatibility with the director’s and/or producer’s approach to the source material. The 1999 version also seems more like a remake of the 1963 version than an adaptation of the novel, taking the “Let’s do all the things the older version of the film couldn’t do” route.

If you’ve seen “The Others,” the 1963 version is a lot closer to that, in terms of tone and style.

@SF Interesting and well-argued points.

I love We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and don’t find it especially scary (though I can well imagine some people may), but I cannot read The Haunting of Hill House at all. Fellow wimps be warned. (Oh, and The Sundial also creeped me out mightily.) Heck, Jackson herself said she had to read Little Women to get to sleep at night after writing sections of that book.

I grew up reading Shirley Jackson’s fictionalized memoirs about her life and children, which are for the most part quite cozy, so her scarier books came as that much more of a shock. But I have enormous, enormous respect for her writing, despite not being able to read a good half of what she wrote.

@HelenS So in your opinion, is Sundial worth a go? I haven’t heard much discussion of it, and I’m ambivalent about the wiki summary, but as you say, I do respect her writing enormously.

@Erin : Personally, I found it took about 5 years, honestly, before I felt really settled over here – and then I had a child and got culture shock all over again! But I’ve readjusted since then. :) And the fact that the two cultures look soooo similar on the surface can make it feel like the earth is shifting under your feet when you suddenly realize you’ve made a major cultural misstep in your new country.

@wizard Clip : Thank you for telling me about finding “Castle” in Dublin! That’s so encouraging.

And @a-j , I really apologize if what I said sounded like I was criticizing British literary culture for not being American literary culture. I absolutely did not mean that! I was being sincere when I said it had been good for me to discover new-to-me authors, and I even think it’s a really good sign about the vibrancy of both cultures that they have different accepted “classics”.

It’s just an oddly disconcerting feeling every time I realize that something I automatically think of as an acknowledged “classic” (because of the literary tradition I absorbed, growing up) isn’t considered that way at all over here…it’s that little mental shake you have to give yourself every time your preconceptions are challenged. Vice versa is just as true, though – if I’d grown up in the UK and then moved to America, I’d have just as much trouble finding some of the wonderful authors who are (rightly) considered “classics” here!

And I’m really glad to have had my literary horizons broadened, both as a reader and as a writer. There are a bunch of authors I absolutely love whom I would never have discovered if I hadn’t moved over here, and my own writing has changed immeasurably because of my 10 years (so far!) of reading voraciously in the UK.

(But ack – sorry about the accidental double-post!)

I have no idea whether The Sundial is any good. I remember nothing about it except completely freaking out at some very ominous scene, which was, I think, not very far into the book, and I sure as hell wasn’t reading any further. It was one of those things where you don’t really have much idea WHY it’s so creepy, but that particular combination of words somehow cold-fingers your guts and makes everything around you horrible.

I don’t do enjoying-being-scared.

@HelenS Yeah, I know what you mean. Sounds really visceral and affecting, at least. :/

Stephanie Burgis@18

And I’m sorry that my comment upset you (it was actually aimed at ErinHoráková@9’s comment:

And my comment was meant to be fairly light hearted but obviously failed to be. As I believe they say in the States, ‘My bad’!

Two of my all-time favorite novels, thanks for this post! When my senior-year high school English teacher had us do dramatic readings I read a few scenes from Hill House, ending on the line “Whose hand was I holding???” I ran almost ten minutes overtime but she didn’t cut me off, and the class vice-president, who’d rarely deigned to notice me, whispered, “That was great!” as I returned to my seat — one of my first moments of geek glory.

That Halloween I watched The Haunting on TV with the friend who’d introduced me to Jackson and her brother, in her darkened bedroom, moonlight shining on an old church steeple just outside the window…. After Julie Harris delivered that line the station cut for a commercial, and in the silence before the ad began her cat scratched at the door. The three of us nearly jumped out of our skins.

We read the scary stuff before discovering Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons, the books about her family. It was deeply satisfying to be laughing our way through books by the same author who’d creeped us out so thoroughly before.

@EAJ/24

Oh, I haven’t read the memoirs! They sound like they might well be worth seeking out!

After you get past the the initial humorous shock of the ending, I think the couple in “One Ordinary Day, with Peanuts” are horrifyingly creepy.

@@@@@ 26. Steve Wheeler –I read it on your reccomendation–it’s available online with a quick google, if anyone else is similarly inspired. The writing’s got her usual strength, but while I liked it well enough, the conceptual simplicity (while obviously approproiate for the length of the piece) put me off a bit?